FOD Operations

Workplace Safety in a FOD Environment

If you are at the wrong place at the wrong time, foreign object debris will easily cause a workplace injury in both aviation and manufacturing environments. Small rocks thrown into the air by rotor wash can attack you like projectile weapons. Dropping a metal tool into an electrical assembly can electrocute you. Cargo that is spilling off a loader can put a big dent in your day, not to mention your skull.

That’s why anyone who works around aircraft, repair stations or assembly lines has an immediate and personal stake in a strong Foreign Object Damage (FOD) control program. A FOD program is successful only if workplace safety tips for employees are taken seriously whether at an airport, hangar, or shop. Regardless of the hazard, safety comes first.

Suggested Resources

Check out our articles on How to Prevent FOD at Your Airport or How to Set Up a FOD Program for more great ideas.

Challenges in Workplace Safety

Ramp areas especially face growing risks of injury, as airlines continue to reduce budgets and increase workloads to remain competitive in a tight air travel market. Some ramp workers are becoming increasingly vocal about their complaints.

At the same time, workers also need to make a personal commitment to behave responsibly and avoid such preventable accidents. One example is a story where a ground vehicle driver died in a crash because he failed to attach his seat belt.

In 2012, a ramp agent at Dulles International Airport died when a mobile lounge collided with his much smaller baggage tug. To this day, airport officials and the victim’s family disagree over who was at fault. The parties involved eventually settled out of court.

The New York Committee for Occupational Safety and Health (NYCOSH) reports that wheelchair attendants complained they received no training and no cleaning materials to handle incidents of blood or other bodily fluids on the chair. In one case, it was reported that employees were forbidden to wear protective gloves, lest it “embarrass” the passengers.

Solutions

Consider publishing a newsletter to improve workplace safety and distributing it to employees, contractors, and tenants. One great example is the Hong Kong Airport Authority’s monthly Airport Safety Bulletin. It provides a useful mix of recent events, such as employee recognition awards, announcements of upcoming audits or drills, reminders of official policy or law, and practical safety tips for airport employees.

Participate in the FAA’s Safety Management System (SMS) project. The goal is to create a formal approach to safety management throughout the National Airspace. Include identifying hazards, analyzing and mitigating risk, and developing aviation safety tips and methods for ensuring continuous improvement.

The UK’s Health and Safety Executive is responsible for workplace safety in Britain. They have assembled links to several useful case studies produced by companies in the air transport industry.

In one study, Air Canada developed a Turnaround Plan for coordinating the separate tasks performed by various individuals and teams during aircraft ground handling operations. This resulted in a steady drop in the accident rate. Nejlepší plinko pokie stránky

In another instance, a serious accident involving an engineer who fell from a cargo hold brought home the seriousness of Virgin Atlantic’s ultimately successful efforts to design better maintenance steps (portable stairways) with moveable guardrails.

NYCOSH has recommended (see the link in paragraph five) specific ways that industry employers can improve workplace safety and training conditions including hazardous materials, infectious diseases, and extreme temperatures. For instance, one recommendation calls for a written Exposure Control Plan for disposing or minimizing employees’ exposure to infectious diseases.

If you have never had the chance to speak with an airport safety officer, this interview at Birmingham Airport in the UK will give you a good idea of the long hours and intense inspections they constantly put in to keep airport operations area safe.

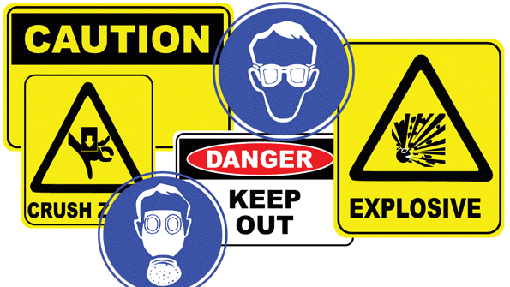

Finally, in some cases you might improve workplace safety with nothing more expensive than improved instructions and a few warning signs. In 2008, an air museum volunteer died after falling off the cargo compartment of a moving aircraft tug. Afterward, the museum painted “NO RIDERS ON BACK OF TUGS” on the backs of its tugs. Here’s hoping that it’s still effective.